Beyond the Runway featuring Mary Kelsay

Threading Traditional into Today

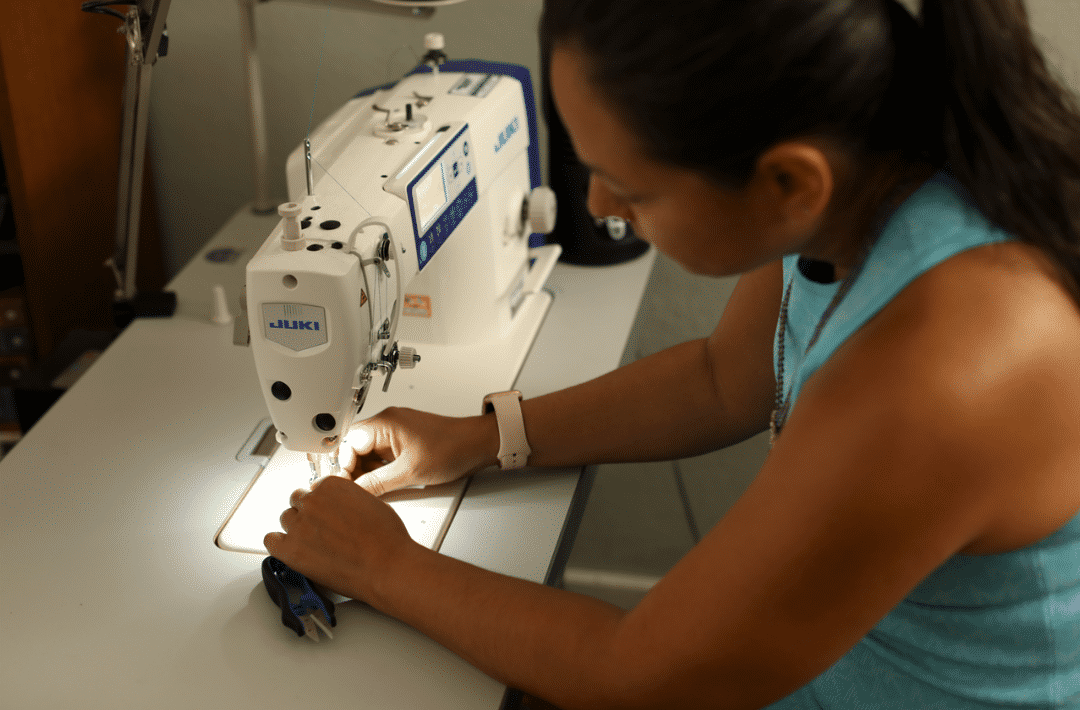

A white sewing machine with gleaming silver knobs purrs quietly on the table in Mary Kelsay’s Seattle workshop. The needle whirs quietly, up, and down, as Kelsay feeds the waistband of a skirt through the machine.

“This is my newest investment,” Kelsay says. “My other machine was—well, is, I still have it upstairs—is a 1967 Singer. It’s old. This is brand new, and it has all the bells and whistles.”

Like her sewing machines, Kelsay’s fashion design is a product of both the past and the present. Mary Kelsay is the owner and designer of MEKA, a clothing company that infuses her Unangax̂ heritage with cutting-edge contemporary fashion.

A red dress, with a line of buttons sweeping diagonally from near the neck toward the waist, hangs on a rack in Kelsay’s sewing room. This is her take on a traditional kuspuk, she explains. A long, sweeping red cape dress also hangs nearby. The elegant dress looks like it would be at home on the streets of Paris, but Kelsay points out that its beautiful dark pearly buttons are made of mussels—common in the Aleutian Islands.

Kelsay admires and respects Unangax̂ makers who work largely in traditional styles and materials, keeping centuries-long

traditions alive, but she sees her mission as different and distinct: she wants to bring the cultural developments and heritage of the Unangax̂ people to a global audience and establish Unangax̂ ways as a valuable part of contemporary global culture. Her clothing, she says, is not intended for museums or exclusive use by Alaska Native people. It is for everyone, here and now.

“We have gut parkas, we have bentwood hats, we have fur, we have the regalia,” she says, praising the iconic traditional products of the Unangax̂ people. “It’s all just beautiful. But I’m not a traditional maker.”

Kelsay’s route to being a leading Unangax̂ contemporary fashion designer was neither straightforward nor easy. Her family comes from Umnak Island, she says, but Kelsay was born in Anchorage and the family traveled often because her father served in the military, taking her from Alaska to Georgia to Washington. At the age of twenty, she found herself in Seattle.

“My mother always told us we were Aleut,” she says, “and that’s who we were, and always be proud. This was enough to establish a connection to her culture—one that would later grow much stronger.

“I did know who I was,” she says.

Kelsay always had an interest in fashion but was stuck in a medical career in pharmacy.

As a child she had dressed up, and crafted small items like purses. “I’ve been in fashion probably my whole life,” she recollects.

But it wasn’t until one pivotal day in Seattle that she decided to turn her passion into a lifelong career. She was working as a part-time fashion model. At a fitting for a shoot, she was smitten by the entire process, the tools, materials, and techniques that a designer used to bring an idea to life from sketchbook to the runway. After connecting years later, this designer became a mentor, fashion partner and good friend.

Having left her medical career, Kelsay enrolled in a two-year design program at Seattle Central College. The program was intense. She describes it as four years boiled down to two, and recalls grueling hundred-hour work weeks spent poring over patterns, making designs, and fabricating garments. But she made tremendous progress, in part due to the excellent quality of instruction.

She “literally had the best teachers in the world,” she says.

Learning about fashion, Kelsay also deepened her connection with her Unangax̂ roots—a process that continues to this day. She has done extensive and

collaborative research on Unangax̂ people, designs, and materials, constantly incorporating her knowledge of indigenous traditions into her contemporary practices.

Around the same time as design school, Kelsay became a shareholder with The Aleut Corporation after being gifted shares. Kelsay became more involved with her corporation. This helped Kelsay feel that she had a direct stake in the corporation’s success. Kelsay began attending yearly meetings and has taken advantage of many opportunities, she says, including funding for school and professional development from The Aleut Foundation. She returns to Anchorage often to attend the Alaska Federation of Natives, annual shareholders meeting, and Culture Camp.

Kelsay loves working with colors, many of which are inspired by the Aleutian Islands themselves: blues and greens from the ocean, the gray of maritime fog, the black of obsidian cliffs, and the tan of beach sand. But there is one color that holds a powerful, if painful, significance in Kelsay’s work: red.

As she grew her ties to her culture, Kelsay became increasingly aware of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women movement (MMIW). This movement aims to bring awareness to and combat the epidemic of disproportionate violence against Indigenous women and girls in the United States and Canada. Supporters of the movement often use the symbol of a red handprint, and incorporate red black into posters and other advocacy materials.

For Kelsay, the MMIW cause is deeply personal. She has had family and friends stolen throughout her life. Even those not directly affected by violence, Kelsay explains, can be deeply impacted by the concern for the safety of loved ones.

“There are many, many, many sisters out there that have been stolen, taken from us,” she says.

Kelsay applauds those who work directly to aid victims. As a fashion designer, she believes she can support the cause by using her design as a platform to spread awareness. Fashion, she says, can be a powerful form of protest and messaging.

The red garments in her studio are part of a collection meant to highlight and support MMIW activism.

“I choose to use my platform to create a conversation,” she says.

Starting this conversation isn’t always easy. Many are reluctant to talk about such a painful subject, even when it impacts them directly. But her efforts have frequently been successful. At pop ups or after fashion shows, she says, attendees will approach her to begin dialogues about MMIW. Some share concerns, some share their stories, some want to know more and listen.

“I want people to be aware that there is a problem,” she says. She hopes that her fashion work can be part of a wider process that brings awareness of the MMIW crisis into the mainstream—and finds real solutions that will keep communities safe.

MMIW advocacy isn’t the only challenging cultural topic that Kelsay addresses with her work. She is sometimes asked difficult questions about traumatic historical events, such as the forced internment of Unangax̂ people in Southeast Alaska during World War II.

In Europe, Kelsay says, knowledge of North America’s Indigenous cultures is particularly thin. This is understandable of course—Europe is an ocean away and Kelsay doesn’t expect everyone to be familiar with every culture in the world. Still, this leaves a lot of ground to cover. “They think of buckskin and teepees,” she says. Many are thrilled to see and hear about Alaska Native culture and fashion.

Showing fashion in Paris for Fashion Week has been a highlight of Kelsay’s career. She was excited to find that Parisians dressed exquisitely, even if it was only to get coffee. She enjoyed working with the models and other fashion arts folks. And, despite the lack of cultural knowledge, she found the people friendly and inquisitive.

“They loved me!” she exclaims, “They loved us. They loved all the indigenous fashion.”

Showing and filming in Paris had always been a career-long dream, and one she hopes she can experience again soon. Kelsay has also shown her work at the Santa Fe Indian Market. This event is one of the largest showings of Indigenous work in the world—if not the largest, she says—and is an incredible opportunity to show her work to a large audience and connect with other Indigenous makers.

Of course, in addition to the challenges and opportunities presented by being an Indigenous maker, Kelsay must still attend to all the hard work of running the business itself. She always knew she wanted to work for herself, she says, and wouldn’t have it any other way. Still, that means overcoming daily challenges. There are some days when it’s hard to get motivated, she says. Working alone requires discipline and organizational skills.

“It’s sometimes hard to get it together. But you have to,” she says.

Working alone also means that, unlike some designers, she does not have a production team executing her designs. She has to do the work herself. To prepare for the Santa Fe show, that means creating approximately two hundred pieces, almost entirely on her own. That includes fifty or sixty dresses, tops, skirts, and other pieces that require many hours to produce. And every piece might require many sketches, mockups, and drafts before the final piece comes into form.

But despite the difficulty, Kelsay has never looked back. The obstacles, challenges, and countless hours of hard work have all led her to her position as a prominent ambassador for Unangax̂ culture and one of North America’s standout Indigenous Artists. At this point in her career, the results speak for themselves.

“Always follow your dreams,” Kelsay advises, “you’re not always on the right path, because sometimes you have to take multiple paths to really get to your dream. And, there will be lots of obstacles along the way but if you really, really hold it in your heart and in your mind, you can do anything. And you can be anything.”