Adaptation: Fishing and Family in the Aleutians

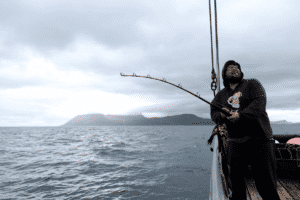

A big motor emits a low, steady purr as the fishing boat crawls steadily forward, leaving swirls of dark water churning in its wake. In the distance, the green mountains and slopes of the Aleutian Islands rise gracefully out of the Pacific Ocean before fading into low clouds.

The boat is painted bright white, with light blue trim. It is the kind of old but well-loved vessel that one might expect to find on a postcard. But this is a true working boat, designed and operated with stark utilitarian efficiency in pursuit of one central goal: catching fish. Lots of them.

find on a postcard. But this is a true working boat, designed and operated with stark utilitarian efficiency in pursuit of one central goal: catching fish. Lots of them.

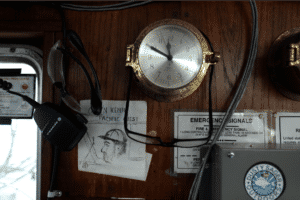

In the wheelhouse, the Captain, Kenny Bob Mack, recalls his first days in the industry over four decades ago, “I was just a young guy,” he says. After 43 years of fishing, he tried to retire several years before. “I quit three years ago!” he claims, breaking into a wide, boyish smile. When friends and family try to remind him of his retirement, he jokes that his memory is going, and he cannot help but get back on his boat. To many in the Aleutian Islands, fishing is almost synonymous with life itself.

Mack is based in King Cove, but he and his family fish from east of Sand Point to west of False Pass. When they tender—collecting fish from other boats to bring to a processor—they might make deliveries as far away as Dillingham on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta in Western Alaska.

Mack explains that decades ago it was possible to make a living fishing only for salmon. But lower prices and unpredictable fishery quotas meant that the boat must be able to function like a giant aquatic Swiss Army Knife—quickly retooling to accommodate a range of species. Cranes, machinery, tables, and other equipment can be installed, uninstalled, or swung in and out to quickly transition the boat between salmon, crab, and halibut fishing.

Many boats also go for black cod, Mack says. Black cod fetches high prices and is growing in popularity due to its high fat content and delicate, sweet taste. Recently, the fishery moved from using hooked longlines to using pots—metal cages—to catch the fish, in order to prevent orcas from eating them off of the lines.

“They’d eat every fish!” he exclaims, “Every fish off the line!”

They haven’t retooled for that species just yet, but they might. For those operating in Alaska’s contemporary fisheries, adaptability is now—as always—a key to survival.

They haven’t retooled for that species just yet, but they might. For those operating in Alaska’s contemporary fisheries, adaptability is now—as always—a key to survival.

Unpredictable fish stocks, coupled with haphazard and last-minute management decisions by State and Federal regulators are a constant challenge, Mack says. The last good year for Tanner crab, for example, was 1987. The fishery took decades to rebound, and even then, the rebound has been sporadic. In recent years the salmon industry has also been in flux, though last year, he says, was a very good year in Bristol Bay. Lots of fish, and many of them were large.

The bureaucracy and complex web of regulations and permitting managed between different levels of government, Mack explains, cause chronic frustration and unpredictability for commercial fishermen. Management decisions are often made by faraway bureaucrats working with incomplete or misleading data, which result in poor outcomes for those who make a living on the ocean.

The red crab fishery, he says, has been shut down for the last year and a half. And there was no red crab or king crab season last year at all. Sometimes fishermen go out fishing only to find fisheries closed or so limited that they cannot make money, leaving them to wonder why they came in the first place. Bureaucrats constantly talk about shutting down fisheries, perhaps for years, leaving the livelihoods of fishermen in constant limbo.

The red crab fishery, he says, has been shut down for the last year and a half. And there was no red crab or king crab season last year at all. Sometimes fishermen go out fishing only to find fisheries closed or so limited that they cannot make money, leaving them to wonder why they came in the first place. Bureaucrats constantly talk about shutting down fisheries, perhaps for years, leaving the livelihoods of fishermen in constant limbo.

“Fish come, fish go,” he says. “We don’t need handwritten rules.”

Mack believes that management and ownership of Aleutian Islands fisheries should still rest with local and Indigenous groups, just as it did for thousands of years. He notes that other Alaska Native groups were given control over land-based resources, but the resources in the Aleutian Islands, which derive almost entirely from the sea, are under the purview of State and Federal agencies.

“Southeast, they got timber. Up in the Arctic region they got oil. Interior, they got minerals. And we ended up with rocks. So,” he laughs, “we should have had fish! And it would have benefitted the whole state.”

Mack believes that villages should always be first in line when stocks are low. But at present, decades of management decisions have given exclusive rights to fisheries to a wide range of entities, including faceless companies in the Lower 48. Mack doesn’t see why outside entities should have special rights to the marine resources that Indigenous groups have fished for many generations. Mack is disappointed that he and his children do not have the same ownership of their marine resources that their ancestors did.

Ultimately, Mack says, people move to where fishing is good. And if his children cannot make a living fishing here, whether it is because the fishery has crashed or fishing rights are held by non-local entities, then they will have to leave too. But for now, Mack is still the captain of the family boat—a position he seems unlikely to relinquish for the foreseeable future. “It hurts to fish,” he says. “But it’s still fun.”

Robert Mack

Below on the deck, Kenny Bob’s son, Robert Mack, demonstrates how they prepare salmon as bait when fishing for halibut. The chum salmon is placed on salt for four or five hours, Robert explains, before cutting it into chunks. The chunks are then affixed to barbed hooks on a long line. The chunks must be attached just right to entice halibut.

“The hook goes in on the skin side, and then we bury it back in the meat,” he explains. “That way there are no sharp points when the fish try to get a bite out of it.”

The line, covered in hooks with chunks of salmon attached, is run out the back of the boat and then later is reeled in with a hydraulic reel.

When they’re fishing in an observed Federal fishery, three cameras record everything that happens on the boat to ensure that laws are being followed. An observer is also present. When there is unintended bycatch, it must be treated properly and swiftly released.

“You have got to pet them and give them a kiss before you throw them back over the side,” he jokes with a smile.

The younger Mack runs his own boat for salmon in Area M, but joins his uncle or father’s crew to fish for halibut. Many boats are family operations, and competition can become fierce.

“There’s a lot of deceiving going on between friends,” Robert explains with a knowing smile, “to not let them come and catch what you’re catching, because you want to be the one to catch it all.”

Regulatory uncertainty and competition aren’t the only challenges they face on the boat. Fishing is hard work, and it can be dangerous. The hooks are razor-sharp and are pulled in and out of the boat with powerful machinery. People have been thrown into the water by hooks or buoys. Crab pots can weigh five hundred pounds and can easily break bones, or worse.

Regulatory uncertainty and competition aren’t the only challenges they face on the boat. Fishing is hard work, and it can be dangerous. The hooks are razor-sharp and are pulled in and out of the boat with powerful machinery. People have been thrown into the water by hooks or buoys. Crab pots can weigh five hundred pounds and can easily break bones, or worse.

“Steel doesn’t say ouch,’” Robert notes.

His cousin was once pulled over the side of a boat by a sea lion while unloading cod at the dock. The animal jumped up, grabbed on to the back of his pants, and pulled him backwards over the low rails of the boat. Late night talk show host Jay Leno contacted the cousin, Robert explained, but his cousin passed up the interview opportunity because he didn’t want to miss out on the fishing season.

Kenny Bob Mack seems nonchalant about the invitation extended to his nephew to appear on one of America’s most-watched television shows. Outsiders are often fascinated by what is—to them—a faraway archipelago surrounded by the Bering Sea and Pacific Ocean. Media that caters to this fascination isn’t always accurate. He comments that much of Deadliest Catch, the highly watched Discovery Channel reality TV series about crabbing in the Bering Sea, feels absurd and scripted. Many of the situations encountered on the show, he says, just don’t happen on typical boats.

“I watch it to laugh at all the things that are done that most boats don’t do,” he says.

For Kenny Bob, there is little need to learn about fishing in the Aleutian Islands from reality TV. He lives and experiences the reality of life in the Aleutians every day.

“I find beauty and awe in all the mountains,” he says, looking out across the water.

Fanny Jo Newton

On the dock, Fannie Jo Newton, niece to Kenny Bob, talks about her recent move back to King Cove. Newton was born and raised in the Aleutians, one of four children in a biracial fishing family. Her mother is Aleut and her father moved to Alaska from Illinois to take advantage of the “crab rush”.

Newton has many fond memories of growing up fishing with her family and other residents. “It’s a pretty neat place to live,” she says, “I’m very lucky to be in a fishing community.”

Now adults, all of Newton’s siblings fish. Her sister helps their father on his boat, while her brothers now run their own boats. Salmon isn’t lucrative enough to make a full-time living anymore so her brothers also crab.

Newton identifies as Aleut, even though, she notes, she doesn’t necessarily “look Indigenous.” This is common in the Aleutians, Fanny-Jo notes, where Russians have had a presence for hundreds of years. The Unangax̂ population is now very diverse. “Even though I might not look it that’s who I identify with,” she says.

“It’s rough when I go to other places and I want to be part of the Alaska Native community,” she laments. “I’m looked at as an outsider.”

Though identity can be complex, Newton says, she has always been accepted in King Cove. The community is the reason she decided to return.

“I moved back to King Cove because I had such a great time growing up here being part of the close-knit community,” she says. Everyone came together to raise kids and she had many aunties and uncles—even if they weren’t blood relatives.

“Everybody was a part of my life growing up here. I wanted to move back and be a part of that as well,” she says, “And be an adult, for the upcoming generations.”

Newton hopes to settle down, raise a family in King Cove, and have children who could enjoy the same kind of communal upbringing that she experienced.

She doesn’t go out fishing every summer, but there are many ways to be a part of a fishing community besides the fishing itself. Her mother runs a local fisherman’s bar, and a business that provides filters to fishing vessels.

“Even being on land,” she says, “there’s still a way to be a part of the fishing community, just by being here.”