The Unangax̂ Man: A Life of Tales and Art

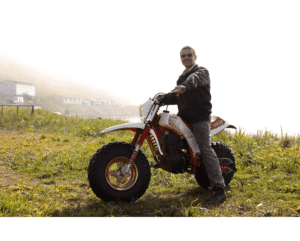

Hugh Pelkey has to live more carefully these days. He has nine lives, like a cat, he says, but he’s already spent eight of them. Now one of the most successful living Unangax̂ artist, Pelkey excitedly recounts some of the harrowing events that have left him with a passionate love for his community, culture, and the Aleutian Islands he calls home.

Hugh Pelkey has to live more carefully these days. He has nine lives, like a cat, he says, but he’s already spent eight of them. Now one of the most successful living Unangax̂ artist, Pelkey excitedly recounts some of the harrowing events that have left him with a passionate love for his community, culture, and the Aleutian Islands he calls home.

After returning to his hometown of Akutan as a young man, Pelkey found his way onto a crab fishing boat. He enjoyed the challenging and lucrative work, but on one trip he fell ill. He became lethargic, his nose bled, and he began speaking incoherently. His crewmates were bewildered when he began talking rapturously about the beautiful sunsets.

As far as the other crew members could tell, the sunsets were ordinary. What they couldn’t see was the inside of Pelkey’s eyes beginning to pool with blood, giving the sky a surreal red tint.

Unbeknownst to him, he was experiencing kidney failure.

On the insistence of the boat’s captain, the boat diverted to Dutch Harbor. Pelkey was upset. “I didn’t want to be blamed for the cancellation of a trip,” he explains, many years later. He was hoping to quickly address the problem and get back to the boat, but after taking his blood pressure, the doctor in Dutch Harbor firmly ruled that out. Pelkey still remembers the doctor’s words: “’I don’t want to get you all hyped up or scared, but I gotta tell you you’re about ready to pop. You have a blood pressure of 260 over 180. I’ve never seen that in the field. Or anywhere.”

Pelkey needed immediate medical attention at a larger facility in Anchorage, but at the Dutch Harbor airport a flight attendant inadvertently put him back on a flight back to Akutan. By this point, Pelkey was delirious and seeing double.

To make matters worse, the deteriorating weather in Akutan prevented a medevac from flying in to correct the mistake. Eventually, the pilot of the Grumman Goose that had taken Pelkey back to Akutan, stricken with guilt at returning a sick man to a town that could not properly care for him, flew back to pick him up.

The weather was atrocious, but the Goose managed to land in choppy seas and take off again, this time with Pelkey on board and headed in the right direction. Pelkey was barely coherent, but he remembers his confusion when he looked out the window only to see that the land below them appeared stationary. The winds were so strong that the Goose was barely able to move forward.

“I thought the Goose was gonna kill me,” Pelkey recounts, “let alone renal failure.”

Pelkey eventually made it to Anchorage, where he was unloaded from a helicopter and into the care of medical personnel at Providence Hospital. He was put on dialysis and entered onto the national donor waitlist. He was told that recovery might last two years. Eventually, his sister offered one of her kidneys for transplant. Pelkey had not asked for the donation, but accepted it. He made a full recovery.

Pelkey was humbled by his sister’s lifesaving gift, but a supportive family and community had always been a part of his life growing up in Akutan. Pelkey remembers his childhood on the island fondly, as a series of beautiful mental snapshots of beaches, green hills, and cozy homes filled with family.

In 1967, when his sisters were old enough to need formal education, the family decided to move to Washington rather than send the children to boarding school.

Pelkey spent thirteen years in Washington with his family, until they were ready to move back to Akutan. Pelkey was initially skeptical. By this point he drove a 1970 American Motors Javelin SST, worked hard at his job, and an active social life in Washington. “I was reluctant to go at first,” he says, “’because of all my friends, I’m leaving what I’m familiar with. But then there’s that inkling. I wanted to get back to Alaska. That connection was important.”

It was the right decision. In 1980, Pelkey boarded an airplane bound for Alaska. It was the first time he had been on an airplane, and it was a thrilling way to return home—made even more of an adventure by a mistake before the final leg. Because of a logistical snafu, Pelkey was separated from the rest of his group and had to spend nine days alone in Cold Bay. Despite having no money, he was able to find a place to stay and enjoy his lengthy and unexpected layover in Cold Bay.

When he finally arrived in Akutan, he was treated to a warm, enthusiastic welcome. “It was the best feeling in the world,” he says, beaming. Everyone had groomed yar ds and flowers, and all the houses in the town were painted white.

ds and flowers, and all the houses in the town were painted white.

“So in the mornings, if you were out in a skiff, and looked back at the village the sun would light the whole village up,” he says. “You could see it for miles.”

As he settled back into life in Akutan, Pelkey became interested in the beautiful handmade kayaks, spears, fox traps, and drums found throughout the community. He was curious about indigenous art techniques and asked local artist, like Bill Tcheripanoff, many questions. But his attention, for now, was locked on something else: crabbing.

After a stint working in the fishing industry, Pelkey decided that he wanted to make more money by crabbing. The work was hard and not without risk, but his first time out the boat caught 5000 pounds of crab. “I was hooked,” he says.

After recovering from kidney failure, he ignored the advice of his doctors and quickly went back to work in the crabbing industry. “I had to make a living!” he explains. He had a wife and a growing family to support.

His kidneys were less problematic this time, but after the boat nearly sank he decided to stop tempting fate. “I think I’d used up eight of my lives at that time,” he says.

He quit crabbing and went to dive school to learn to be a commercial diver, a job he held for 21 years. Pelkey also lived and worked in Washington State and in Anchorage, but it was never a good fit. Pelkey disliked the “rat race” in Washington, and despite the friends and opportunities in Anchorage, the big city didn’t feel right. People didn’t take the same pride in their work and community in other places. “I just couldn’t..” he starts to explain, and trails off.

Akutan was home.

Around the year 2000, living back in Akutan, Pelkey began seriously investigating local art traditions. It was hard work, made especially difficult because much of the finest work had been traded away for goods or purchased by collectors and institutions. Pelkey pored over microfilms of artwork, attempting to reverse-engineer traditional practices from the blurry slides. He began crafting spears, drums, and other objects.

Around the year 2000, living back in Akutan, Pelkey began seriously investigating local art traditions. It was hard work, made especially difficult because much of the finest work had been traded away for goods or purchased by collectors and institutions. Pelkey pored over microfilms of artwork, attempting to reverse-engineer traditional practices from the blurry slides. He began crafting spears, drums, and other objects.

Though Pelkey was working hard to teach himself Unangax̂ practices, this was not his first foray into art making. His mother had created freehand artwork and pottery, introducing him to art at a young age in their home. Pelkey traces his artistic awakening back to third grade, when he began drawing on desks. At first, his teacher made him stay after class to clean them off. But when he continued drawing on the desks the next day, rather than punish him the teacher bought him art supplies. She encouraged Pelkey to draw anatomical pictures of internal organs, an assignment that he was enthusiastic to complete. The teacher laminated his artwork and hung it up on the wall in the school, he says, where it remains to this day.

In seventh grade, Pelkey’s mom took the family to Southeast Alaska. “I was just floored by the Native crafts in Southeast Alaska,” he says. The masks and drums left a deep and lasting impression on him. Back at home, Pelkey carved a small totem pole with the family’s knives. His mother, who had spent time interned in Southeast Alaska and had been picked on in boarding school, chastised her son for working in another culture’s artistic traditions. Pelkey stopped carving after that, but the passion for creating art had only become dormant. Eventually, back in Akutan, it re-emerged.

Pelkey took his art as seriously as he took his crabbing, and he rose to prominence in the Unangax̂ art world. His hats, spears, and other crafts are highly sought after by art buyers around the world and command high prices. In part, this is because of Pelkey’s devotion to traditional methods and styles. From books he learned where to find ochre, which he makes into water-based paints with hues ranging from yellow to dark maroon. He also uses local obsidian, from a cliff that is renowned throughout the Aleutian Islands for the quality of its stone, and local chert, a softer, slate-like material that can be carved and then hardened in a fire.

Occasionally, pragmatism leads Pelkey toward the use of nontraditional materials and methods. Modern glue, for example, is hard to beat. “I’m not using cod eyes and fish slime,” he says. “I’m actually using industrial glues. So…” he shrugs with a smile, “it’s the only difference.”

Pelkey admires his fellow Unangax̂ artists: Gertrude Svarney and her carvings, Andrew Grondholt and his bentwood hats, among others. But he laments that some artistic traditions have simply been lost. He had to learn how to make arrows from an indigenous man in Washington, since nobody in Akutan still remembered the traditional techniques.

Pelkey knows a little Unangam Tunuu and wishes he knew more. “I blame my generation for losing the language here in Akutan,” he says. He wishes he knew more so he could pass it along to younger people, and hopes that his art practice “makes up” for some of his inability to pass along all aspects of his culture.

Though Pelkey may not be as connected to every aspect of his culture’s history as he wishes, there is no question that he is deeply connected to the land. His adventures—and misadventures—have given him an extraordinary sense of the timeless challenges and joys of life in the Aleutian Islands.

Sitting in his studio, twisting a spear in his hands, Pelkey recounts one of his more extraordinary near misses in the outdoors.

Once, Pelkey and a friend took a small skiff along the shore to hunt for seal. The friend dropped Pelkey off on a small rocky outcropping some distance from shore to hunt. But the friend did not return. Suddenly, Pelkey saw the friend emerge at the top of a rocky cliff on a shore. The boat had drifted away and was lost. The friend said he would run back to town for help—a distance of many miles through deep snow. His friend disappeared. Pelkey waited for some time, but eventually realized he wouldn’t survive if he stayed on the rock.

He jumped in the water and swam to the shore.

Pelkey’s boots filled with water and dragged him underwater. He thrashed through the water, barely reaching the edge of a submerged ledge. He thrust himself upward, gasped for air, and eventually reached the shore.

He began walking along the shore, but found himself trapped by sea cliffs. He jumped back in the water and traversed the cliffs, only to emerge on the other side exhausted and hypothermic. He cleared the snow off of the ground, sat down on the frozen grass, and began hallucinating that he was in a ZZ Top rock concert. In the hallucination, one of the speakers was buzzing. Pelkey realized that it wasn’t a speaker—it was the sound of a boat.

Pelkey fired his rifle, first over their heads and then just off of the boat’s bow. Two men in the boat wheeled the boat around and pulled up to shore. But after Pelkey told them he had lost the skiff; they simply wheeled the boat around and left to look for it. Pelkey once again found himself alone.

wheeled the boat around and left to look for it. Pelkey once again found himself alone.

He woke to find the two men loading him into their skiff. He had passed out from hypothermia and his limbs had stiffened. The men were crying, thinking he had died. They were overjoyed to find that Pelkey was still alive—if barely.

Now all in the boat together, they went looking for Pelkey’s friend. They spotted his footsteps, leading directly into an avalanche path. At the bottom of the avalanche path, they found him—alive but so hypothermic and delirious that he started fighting his would-be rescuers.

Back in Akutan, all four men were treated for hypothermia. “One of my eight lives stories there,” he laughs.

Now an established artist closely guarding his “ninth” life, Pelkey is more focused on encouraging the next generation to continue the tribe’s cultural and artistic traditions.

“What I want to say to the next generation is pick up the ball! And run with it!” he says. He says that he tells the young Unangax̂ people, “You’re rich… you’re rich culturally. You don’t know what you have… you’re rich in that way. You’re culturally rich.”

He hopes to be able to mentor a young person in traditional Unangax̂ art practices. Nobody has come forward yet, but Pelkey holds out hope. “Get educated,” he says, “Know where you come from. And apply. And drive yourself… because you ain’t getting nowhere if you don’t.”