Reinvention featuring Gertrude Svarny - Ludaaĝix̂ (Great Elder)

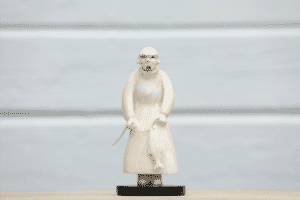

Beautiful sculptures, bentwood hats, jewelry, and weavings created by Gertrude Svarny fill museums and private collections throughout Alaska. To name a few of her accomplishments as a renowned Unangax̂ artist, Gertrude has won

Beautiful sculptures, bentwood hats, jewelry, and weavings created by Gertrude Svarny fill museums and private collections throughout Alaska. To name a few of her accomplishments as a renowned Unangax̂ artist, Gertrude has won

several Best in Show prizes at the Trail of Tears Art Show for sculpting. She was awarded the Distinguished Artist Award from the Rasmuson Foundation in 2017, and she has sat on the board of the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Gertrude Svarny is widely respected for her contributions to preservation, awareness, and education for Unangax̂ culture and art.

Now 92, Gertrude sits in her comfortable Unalaska home surrounded by artwork. But her path to becoming one of Alaska’s foremost Alaska Native artists was long and, in many ways, unexpected. It includes a childhood filled with joy and hardship, a passion for reviving Unangax̂ cultural practices, and a chance encounter with a whale bone.

Gertrude Svarny, née Hope, was born in Unalaska in 1930. Her father was a U.S. serviceman named Charles Hope. Her mother, Alice, was Unangax̂ from Saint Paul. She remembers growing up in Unalaska with a feeling of nostalgia and joy. The children played outside, and families picnicked, picked berries, fished, and swam in the bay. “I had a good childhood and a great mom and dad.”

But that idyllic childhood was shattered in the early 1940s, when Japanese forces invaded the Aleutians. In 1942, American authorities forcibly relocated nearly a thousand Alaska Native residents of the Aleutian Islands to Southeast Alaska. Because Gertrude’s father was a white civil servant, he had to stay behind. But anyone deemed by the U.S. government to have more than 1/8 Aleut blood was required to evacuate.

Gertrude, along with her mother and siblings, had to board a ship bound for an uncertain future.

For the younger children, the relocation had an element of adventure. It was their first time on a ship, and once they reached Southeast Alaska, their first time seeing trees or frogs. But despite the excitement, Gertrude recognizes that “it must have been hard on the older people.” After several weeks at their first destination, the Wrangell Institute, the villagers were taken to an abandoned cannery at Burnett Inlet. Illness ran rampant in the overcrowded facility, and they did not have adequate tools or supplies.

“There were about fourteen to eighteen kids who slept on the floor,” Gertrude recollects, “and we could see the stars through the breaks in the ceiling. They did not prepare anything for us. They just took us and dumped us there.”

Despite the new hardships in this unfamiliar environment, the Unangax̂ people worked hard to improve their living conditions. They built and repaired houses, and packed in fresh water. That fall, the children were sent back to the Wrangell Institute for schooling. Gertrude recalls her education being interesting, but that she often went hungry.

After World War II ended in 1945, the U.S. military abruptly informed the Unangax̂ villagers that they would be taken back to their homes. “We just never knew anything,” Gertrude says. “They didn’t tell us anything.”

Upon returning home, her family found that looters had entered their home and stolen her father’s irreplaceable photographic negatives while he was at work. But the family was lucky; because Gertrude’s father had remained behind in Unalaska, he had been able to protect their home as best as he could. Other homes had been ransacked so badly that they were no longer inhabitable.

Upon returning home, her family found that looters had entered their home and stolen her father’s irreplaceable photographic negatives while he was at work. But the family was lucky; because Gertrude’s father had remained behind in Unalaska, he had been able to protect their home as best as he could. Other homes had been ransacked so badly that they were no longer inhabitable.

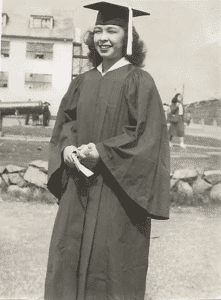

After the war, Gertrude attended Mt. Edgecumbe, a boarding school founded to educate Alaska Native children. “I was stunned that they even considered me. I couldn’t believe it, really!”

But Gertrude thrived at the school and says that overall, it was a positive experience.

At Mt. Edgecumbe, she was able to meet students from around Alaska for the first time in her life. “There were people from up north, and Tlingits, and Athabascans. And many of them were very good friends. We had a really close-knit class.”

As a member of the first graduating class, Gertrude enjoyed helping to build the school’s traditions. It was also the first time she attended an Alaska Native Brotherhood meeting, and the beginning of her awareness of how politics would shape the future of the state. In 1948, she graduated salutatorian—the next highest-ranking student behind the valedictorian.

Despite the hardships caused by the forced relocations years before, Gertrude’s family remained fiercely patriotic and proud of their American identity. Her two brothers followed in their father’s footsteps and joined the U.S. Navy, one serving on an aircraft carrier and the other on a submarine. Gertrude herself married a serviceman in 1950 named Sam Svarny. Sam was an honored veteran of World War II and would go on to serve in the Korean and Vietnam wars.

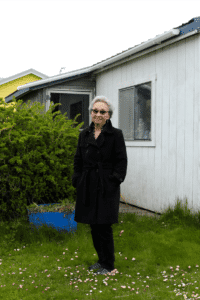

In 1980, the couple left Seattle and returned to her childhood home in Unalaska. The town had changed dramatically in recent years, transformed from a sleepy village of a couple hundred to a thriving boomtown and commercial fishing hub. “I think I learned how to swear when I came back,” Gertrude laughs, “‘cause of the type of people that were here. They were fishermen… they were fine people, but a different way of life.”

Despite the changes, Gertrude and Sam couldn’t have been more excited to be a part of Unalaska life. “We were very happy,” Gertrude explains, “and I was lucky that my husband loved it here as much [as I did].”

Gertrude had never studied art before, but in Unalaska, she enrolled in a painting class and discovered a passion for creating artwork. She enjoyed experimenting with an old set of paints, and primarily saw her work as a source of personal satisfaction. But her career as a professional artist would soon launch in dramatic fashion, in part due to a lucky find on the beach.

During a walk with Sam, Gertrude stumbled upon a weathered fragment of whale bone that had washed ashore. She brought the whale bone home and began sculpting it into a mask with the tools she had on-hand, which included an X-ACTO knife and melon baller.

Gertrude was encouraged to enter her sculptures into a local art show. To her surprise, the pieces sold before the show opened.

This initial success with a traditional Unangax̂ medium inspired her to learn more about the artistic traditions of her ancestors and incorporate them into her work. The whale bone that helped her begin her art practice was rare, so she began sculpting with more accessible materials like driftwood, ivory, and soapstone. Sometimes, she had to wait for months for materials to arrive. But when they did, she enthusiastically set about turning them into original works of art. Sam was supportive of his wife’s newfound career and built a small studio addition for her onto their home.

This initial success with a traditional Unangax̂ medium inspired her to learn more about the artistic traditions of her ancestors and incorporate them into her work. The whale bone that helped her begin her art practice was rare, so she began sculpting with more accessible materials like driftwood, ivory, and soapstone. Sometimes, she had to wait for months for materials to arrive. But when they did, she enthusiastically set about turning them into original works of art. Sam was supportive of his wife’s newfound career and built a small studio addition for her onto their home.

Gertrude and Sam thrived in Unalaska. For one Father’s Day, Gertrude used the proceeds from art sales to buy her husband a boat, which they named “Salmoneye” after Sam. The young couple fished and clammed together, and Gertrude also spent countless hours picking berries and processing salmon with their children—passing on many of the same subsistence traditions that she had learned growing up.

Gertrude remembers those days fondly. “Love the life, love the weather… sometimes,” she says with a smile, “love the people, love the way of life.”

In addition to sculpting, Gertrude started weaving and learned to make jewelry and bentwood hats. She ground ochre, a naturally occurring red mineral found in rocks, by hand to make red pigment, which she incorporated into her work. Because Unangax̂ culture had been so radically disrupted, she had few firsthand sources of traditional art instruction. So she turned to photographs and books. Her research gave her a deep appreciation for the skills and determination of the Unangax̂ people.

In addition to sculpting, Gertrude started weaving and learned to make jewelry and bentwood hats. She ground ochre, a naturally occurring red mineral found in rocks, by hand to make red pigment, which she incorporated into her work. Because Unangax̂ culture had been so radically disrupted, she had few firsthand sources of traditional art instruction. So she turned to photographs and books. Her research gave her a deep appreciation for the skills and determination of the Unangax̂ people.

“I think about how our people used to live,” she says, “and I am just amazed at what they did and often lots of times I just wondered how they could manage to carve what they did. And I thought they’re very, very smart people.”

As Gertrude’s art practice and understanding of Unangax̂ culture developed, so too did Unangax̂ political power. In 1971, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) established thirteen Alaska Native regional corporations (ANCs) to represent the state’s indigenous population. Indigenous residents from the entire Aleutian Island chain and the westernmost section of the Alaska Peninsula became shareholders in The Aleut Corporation.

Gertrude remembers the first dividend payment in 1981 and is grateful for the awareness that the corporation brought to the value of the Unangax̂ way of life. She is also appreciative of the educational opportunities provided by  the corporation.

the corporation.

Still, she says, defending the culture and autonomy is a never-ending challenge. “They did the best they could. But I thought that we owned everything here,” she says. With the passing of ANCSA, Gertrude realized how much land the government claimed during the war; it came as a shock, “[The land was] just… gone. Now I think, we’re kind of having to fight to keep it, too.”

Gertrude hopes that future generations will educate themselves about Unangax̂ culture and pass that knowledge along to their children. “We were really a special people and pretty tough survivors to go through everything that we did… we had the Russians and then we had the war. And, you know, just really a lot of different things and… we’re still here,” she smiled.