Resurgence

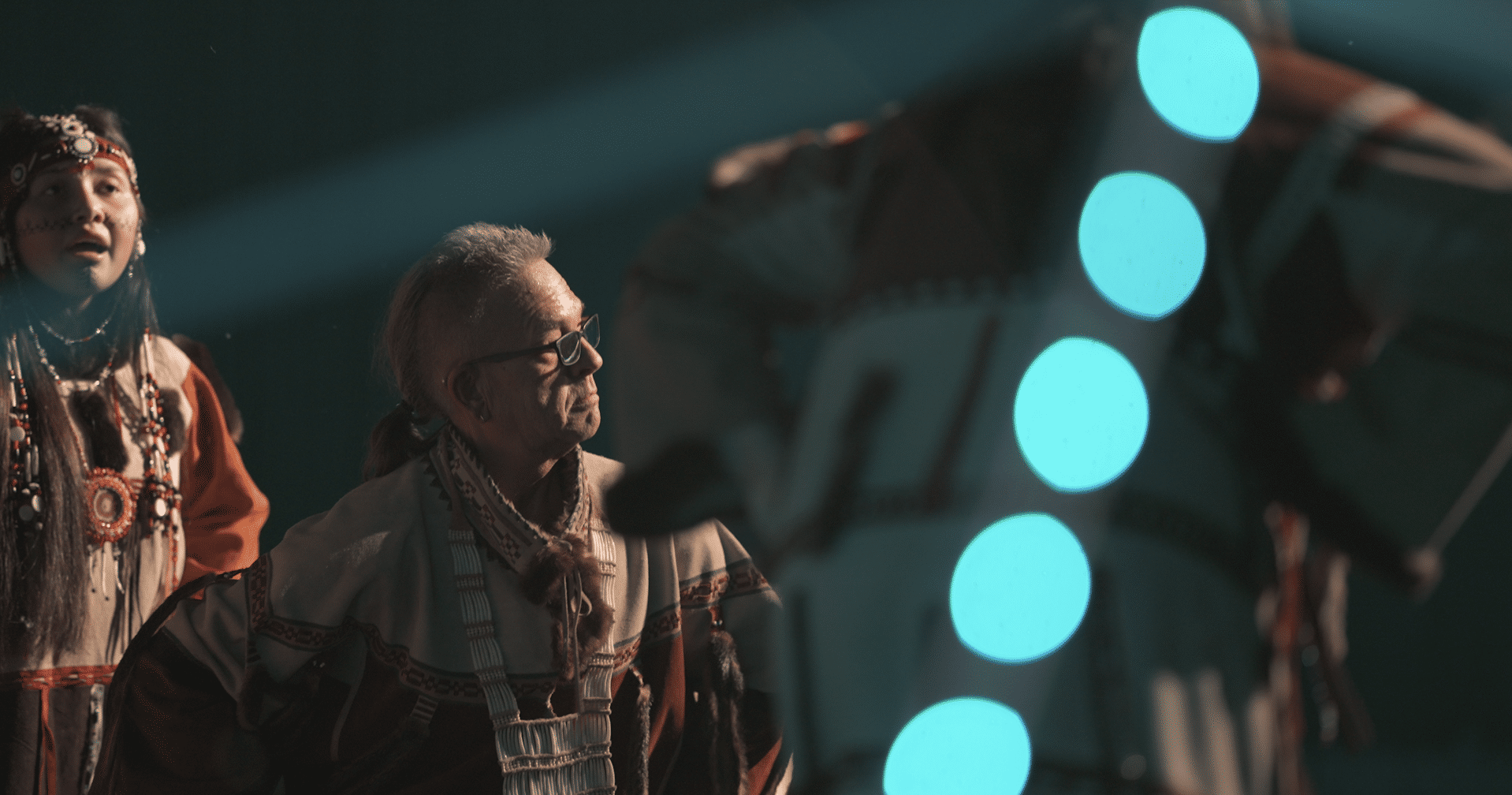

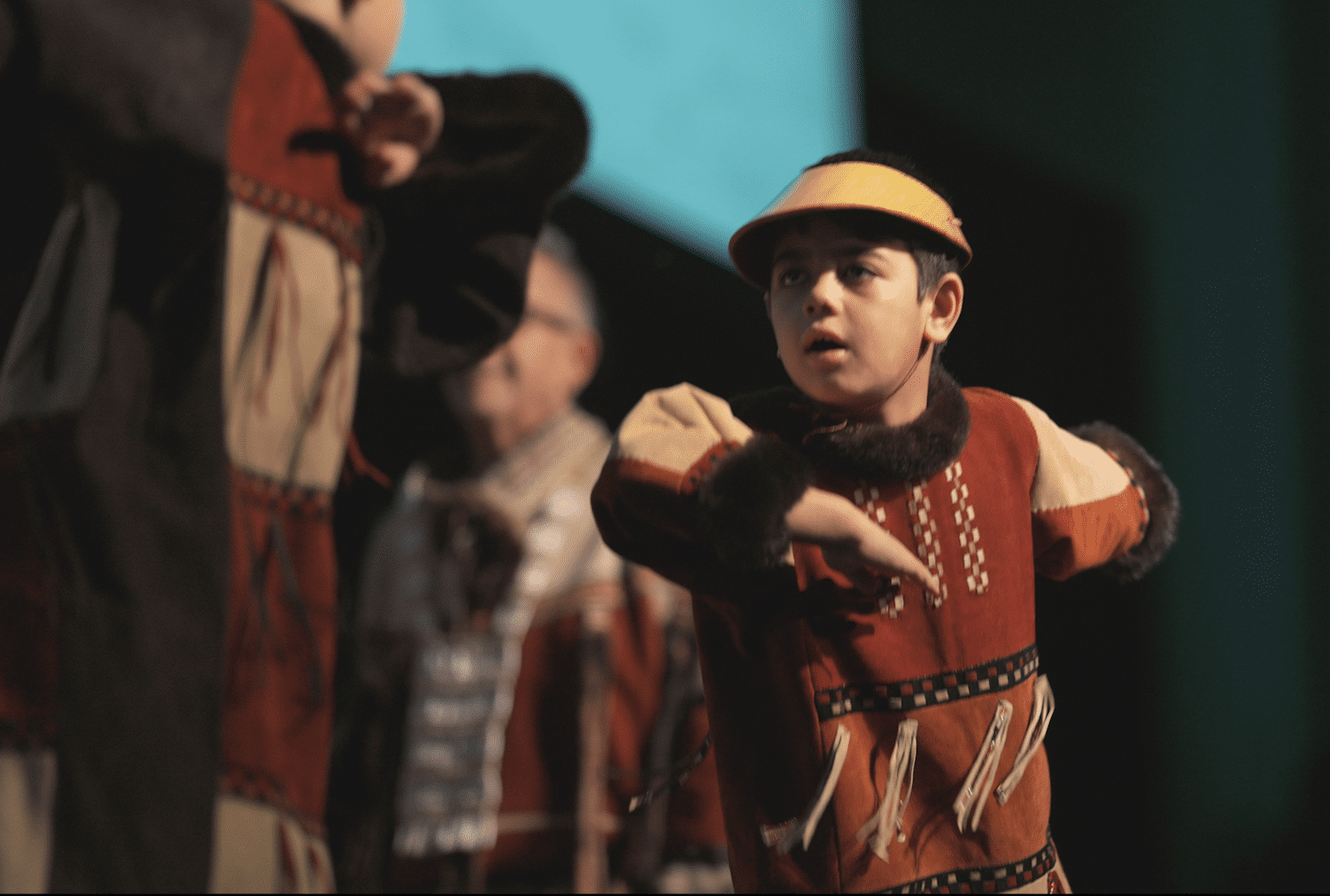

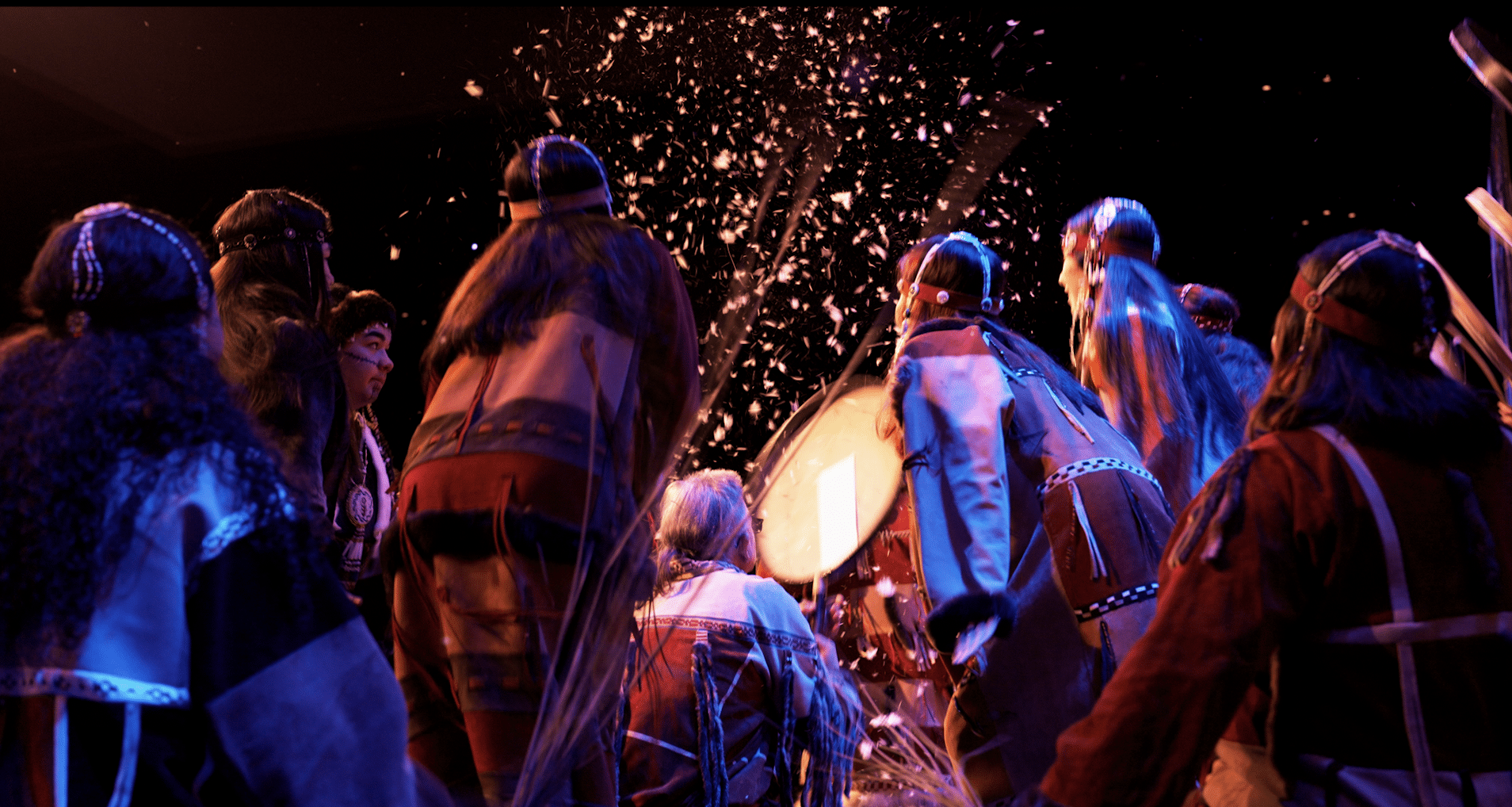

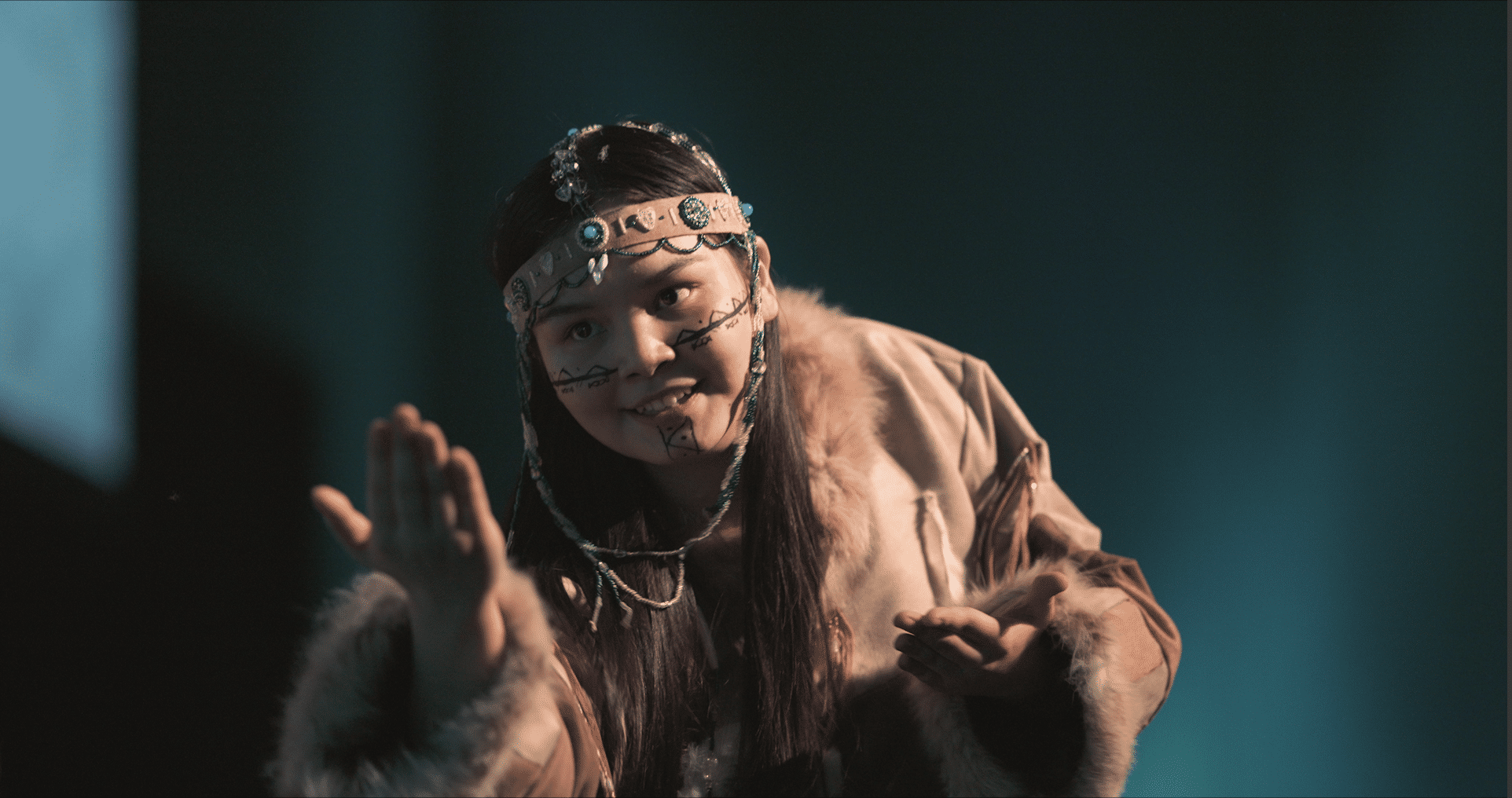

In the rehearsal space, a large group of adults wearing traditional Unangax̂ regalia and bentwood hats pound drums and sing. The melody rises and falls like ocean swells, punctuated by staccato cries imitating the gulls that live in the Aleutian Islands. A boy wearing a colorful hat stands nearby, face painted in a dark mask. At first, he appears bashful, looking around as he gingerly waves a pair of white feathered fans.

The music and dancing stops, and the instructor, Ethan Pettigrew discusses the performance with several of those assembled. They come to a consensus about how the song should be structured, and Pettigrew relays the new instructions to the performers. Just like he has been doing for decades.

The music and dancing stops, and the instructor, Ethan Pettigrew discusses the performance with several of those assembled. They come to a consensus about how the song should be structured, and Pettigrew relays the new instructions to the performers. Just like he has been doing for decades.

“We have to have lots of energy when we sing it,” he says. “This is gonna set our tone for the night. And remember it’s about our ancestors, so let’s lift them in there and pull them in with us.”

The drums resume, and the chorus begins again. A loud, wavering call rises above the underlying melodies. The sound is beautiful and timeless, reflecting the Aleutian Islands themselves and the unique culture that developed over thousands of years. But still, to Pettigrew, it’s not quite right.

Ethan Pettigrew is the dance instructor for the Unangax̂ Dancers. Although based in Anchorage, the Unangax̂ Dance group includes members from across the region. He welcomes all Unangax̂, he says “it’s your birthright” to practice and learn to dance.

“We need to get it down at least once more before we go,” he says. The discussion continues.

Voices and drumbeats fill the room. The time and dedication have paid off. As sound again floods every corner of the rehearsal space, two men in an open area begin dancing in unison, waving fans. The boy, no longer bashful, joins them. He confidently waves his fans from side to side, occasionally glancing at the adults to mirror their movements.

Though this scene might strike contemporary observers as part of a long, healthy, and continuous cultural practice, only a few short decades ago it was all but unthinkable. For a significant portion of the twentieth century, many Unangax̂ traditions—including song, dance, language, and art—came perilously close to being lost. It was only through extensive scholarship, hard work, and a renewed sense of cultural self-respect that many Unangax̂ practices were saved, and are now practiced and passed on to the next generations.

Sitting in her Anchorage home, Sally Swetzof of Atka recalls how she had been “brainwashed” as a young mother not to pass Unangam Tunuu or cultural traditions on to her children. She and her husband, Michael Swetzof, had been told that they should teach their children English, she says, so that they would have a chance at succeeding in a Western economic and social system.

Sitting in her Anchorage home, Sally Swetzof of Atka recalls how she had been “brainwashed” as a young mother not to pass Unangam Tunuu or cultural traditions on to her children. She and her husband, Michael Swetzof, had been told that they should teach their children English, she says, so that they would have a chance at succeeding in a Western economic and social system.

“As a young parent, naturally you want your children to be a success,” she recalls, “you want them to be better than you.”

Swetzof began speaking to her first child, Crystal, in English before she was even born. Many people in the community, she says, were made to feel ashamed of their language and went as far as hiding subsistence foods from outsiders.

“We were made to feel embarrassed of our language and our traditions,” she says.

One day, Swetzof was boiling sea lion at home when the schoolteacher, who was from outside the community, pulled up to the house. Swetzof panicked. She turned off the stove, and tried to drive off the smell. According to Sally, Crystal, now about twelve, asked her mother “’so what’s wrong with that!? This is your house. This is your way of life. Don’t try to hide it, don’t be embarrassed by it!’”

Swetzof realized that her daughter was correct. From that day forward, she says, she decided not to be embarrassed by subsistence foods. “Let them smell it!” she says with a laugh, “I’ll never hide my language or my culture anymore.”

One day, Swetzof recalls, she was watching a broadcast of the Anchorage Federation of Natives (AFN) convention with her daughters. The broadcast included dancers from Yup’ik, Inupiat, and Southeast Alaska groups—but no Unangax̂ dancers.

Undeterred, her two daughters, Crystal and Marii, began drumming with household items.

Undeterred, her two daughters, Crystal and Marii, began drumming with household items.

The Swetzof family decided that they wanted to contribute to the revival of Unangax̂ song and dance. Sally’s husband, Michael Swetzof, who served as the first president of The Aleut Corporation and later on the Aleutian Region School Board, traveled to Kamchatka, Russia, and to St. George Islands looking for elders who had traditional Unangax̂ cultural knowledge. He was not alone on the trip or in his mission. The community had a vested interest to bring back their dormant traditions.

Together, they scoured archival media and brought a skilled dancer and instructor, Katya, from Russia to help the effort. Katya spoke neither English nor Unangam Tunuu, but using a rudimentary program on a 1990s Apple computer, they were able to translate between Russian and English. Katya was particularly influential in taking dance fundamentals—balance, movement, fluidity—and helping to apply them to Unangax̂ dance.

Katya taught the kids with Ethan Pettigrew, finding out whatever they could from old films and audio recordings. Michael used his position on the school board to help integrate Unangax̂ culture into the standard school curriculum. The school district purchased sea otter and fur seal pelts, and the community crafted regalia for the children.

Lacking extensive source material, they created many performances from scratch. One memorable song, Sally says, recounted Crystal’s attempt to harvest king salmon as a child. On her first cast, her daughter caught a fish. She refused help reeling the fish in, but Sally wanted to assist and grabbed the line. The fish escaped. “I just wished the sand could open and swallow me up, because I made her lose her first king,” Sally recollects with chagrin. Though the memory was painful, it became the basis for a cherished original song.

The Atka dance group that formed from these efforts had its first performances in the late 1990s. It was wildly successful.

“Everybody loved it,” says Sally. Elders cried with joy when seeing their traditional song and dance performed again after so long.

“It was like we woke up again from sleeping,” Sally says. “It was a beautiful experience to have.”

Sally is proud of the role that her family helped play in reviving and strengthening traditional Unangax̂ practices, and hopes that younger generations continue their efforts. “People my age and older would like to see the younger generation learn as much as possible about our culture,” she says.

Sally believes that the Unangam Tunuu language is the bedrock of their culture, and that preserving it is key to ensuring the survival of Unangax̂ ways of life. “Once the language dies,” she says, “culture dies. Everything you do in the Unangax̂ culture—the dancing, the traditional foods, the church services—takes language.”

Sally notes that some Unangax̂ people live a more traditional way of life, while others have embraced and integrated with Western customs. She hopes that however young people choose to live, they remember, honor, and pass on their Unangax̂ heritage.

“Don’t forget where you come from,” she says. “Who you are.”

Sitting on a patio in Anchorage, with children playing and singing behind them, sisters Marii and Crystal—now adults with children of their own—explain that wherever they are, they feel a deep connection with Atka, their home on the Aleutian Islands.

Crystal lived in Anchorage for seven years, she says, but wanted to move back to Atka because of “the land, the island, and the traditional foods we have back home.” She loves the culture and community on Atka: how people share food, and provide for and help one another. She loves subsistence foods. But she also feels a powerful draw to the land.

“The island itself is such a big part of who we are,” Crystal explains.

The sisters joyfully recall their involvement with the revitalization of Unangax̂ song and dance on Atka. The work was hard, but the results of the community’s efforts made everything worth it. While Atka was revitalizing Unangax̂ dance, efforts were happening simultaneously in other parts of the Aleut region. Today, several Unangax̂ dance groups exist, preserving and passing on Unangax̂ traditional dances.

“I felt that fulfillment of what had been missing,” Crystal says. “Sometimes you’re missing something, you don’t even know what it is until it happens.”

“I don’t think you can put it into words,” Marii says, wiping away a tear. “It’s pretty indescribable.”

Crystal and Marii are excited to see that Unangax̂ song and dance is not only preserved for the Unangax̂ people, but can be shared with the world. Many people today, they explain, still don’t know who Unangax̂ people are. But they have now shown their dance as far afield as New York and Washington, D.C., and have performed for Australian and Indian dancers.

“There’s a whole world out there,” Marii says.

Crystal and Marii note that the Unangax̂ cultural practices that have been revived in recent decade are no longer part of specific school courses or community programs. They have simply become part of life in the Aleutian Islands. Everyone takes part in keeping traditional practices alive. Now, as the next generation grows up having always known Unangax̂ song, dance, and other traditions, both Crystal and Marii see a bright future.

Of course, it will take work and dedication. The modern world is relentless, Marii says. “Technology keeps getting quicker, and faster, and bigger.”

Crystal hopes that future generations will say connected to their culture and heritage. “And now our dancing as well,” she adds. “It’s so important to keep this connection and keep all this knowledge alive.”

“So that it continues,” she says, “And never ends.”

Crystal and Marii have cause for optimism: many young Unangax̂ have embraced traditional cultural practices. In a quiet room with other students in the background, Charlotte Rutherford slides an elaborately beaded headdress over a glass mannequin head. She is creating an Unangax̂ headdress for a performance, she explains. Another headdress, made of a dense lattice of pink, blue, and white glass beads, is much heavier and covers the whole head and neck. The large quantity of beads, she says, is a sign of wealth.

Charlotte’s father is Yup’ik, and she grew up attending his family’s potlucks and other gatherings. She always enjoyed the sound of drums, and began learning dances when she was twelve. At first, she was shy, she admits, going through the motions out of sight of the other dancers. But with the support of family and friends—and instructors at Culture Camp—she gained confidence and developed a passion for dance.

“I like the Unangax̂ dancing because it involves more movement,” she says. She finds it less repetitive than some other types of dances, and feels that “there’s a lot more action going on.”

Learning Unangax̂ dance is more than just dance, though. Charlotte says she had to make a kuspuk, mittens, and woven fans with feathers in order to dance.

Charlotte is currently a junior at Service High School in Anchorage. She enjoys school, though the Covid-19 pandemic made the transition from junior high difficult. She didn’t get to have her first year of high school in person. And she has lost friends who do not understand her deep bond with her Unangax̂ culture. Once, she says, she came back to school excited to share what she had learned at Culture Camp with classmates. But some thought that the traditional clothing was “weird.”

It’s upsetting to lose friends, Charlotte says, but her connection with her culture is strong and resilient. She knows that people in her grandparents’ and parents’ generations were discouraged from practicing their way of life, and understands that plays a vital role in keeping Unangax̂ traditions alive. “I really am appreciative of the opportunity to learn everything and do everything,” she says.

She explains that a traditional headdress can weigh up to fifteen or twenty pounds, because of the weight of the glass beads. But the headdresses are beautiful, and the weight makes the beads sway perfectly. As she speaks, she works diligently crafting a whale with ivory. Blue beads represent water coming out of its spout.

Charlotte says she enjoys learning the Unangam Tunuu language, and learning more about dance and the regalia. But, she says, she also has a new passion: helping others learn, too.