The Road featuring Etta Kuzakin and Della Trumble

The Road to King Cove

When Etta Kuzakin unexpectedly went into labor with her third child, she faced a terrifying choice. In most American towns, getting to a hospital for a C-section operation would be a matter of simply driving to the nearest hospital. But Kuzakin didn’t live in an ordinary American town. She was in King Cove, Alaska, a village of about a thousand in the Aleutian Islands, and reaching the nearest hospital would require a medevac flight from the town of Cold Bay. Though the large runway at Cold Bay was only fifteen minutes away by air, poor weather made traveling by aircraft or boat all but impossible.

When Etta Kuzakin unexpectedly went into labor with her third child, she faced a terrifying choice. In most American towns, getting to a hospital for a C-section operation would be a matter of simply driving to the nearest hospital. But Kuzakin didn’t live in an ordinary American town. She was in King Cove, Alaska, a village of about a thousand in the Aleutian Islands, and reaching the nearest hospital would require a medevac flight from the town of Cold Bay. Though the large runway at Cold Bay was only fifteen minutes away by air, poor weather made traveling by aircraft or boat all but impossible.

And so Kuzakin was faced with a choice: should medical personnel in King Cove prioritize her life, or the life of her child?

For Kuzakin, who now serves as the President of the Agdaagux Tribe of King Cove, there was only one option. “So, I made sure the medical staff understood that if something happened, they should take my life and not my daughter’s,” she says, struggling to hold back tears even years later. “Because as a mom that’s what you have to do.”

Luckily, at the last minute a Coast Guard plane was able to divert to King Cove. Kuzakin was flown to Anchorage, and both mother and daughter survived.

“These are the choices that I don’t think anyone should have to make,” Kuzakin says, “but we do.”

Others have not been as fortunate. King Cove sits at the boundary between the Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea, and the collision between different climates often creates strong winds, fog, and thick clouds. Rugged and mountainous topography around the airfield form perilous obstacles and can generate unpredictable and dangerous crosswinds. Planes can drop suddenly out of the air, crashing onto the runway, or get lost in the fog. Travel between King Cove and Cold Bay is often dangerous or impossible, and during emergencies, when every second counts, the lack of transportation can be devastating.

In one period from 1980-1994 alone, a dozen people died during medevac attempts between the two towns. Residents of King Cove can gesture up at the mountains, pointing out locations where medevac planes have crashed, killing those on board.

Even when medevacs are successful and patients survive, incidents can be extraordinarily expensive, and can leave people traumatized or in worse health than they would have been if they had been able to reach help more quickly.

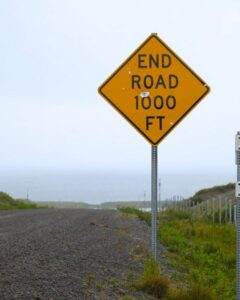

The tragedies that have unfolded in King Cove over the decades are compounded by one infuriating fact: according to King Cove residents, many of them are preventable. Existing roads nearly connect King Cove to the all-weather airport at Cold Bay, but a twelve-mile segment in the middle is missing. This 12-mile stretch would run through the Izembek National Wildlife Refuge.

For Kuzakin, completing the road is an achievable goal and an essential component of ensuring fairness and quality of life for the residents of King Cove. As the President of Agdaagux Tribe, Kuzakin is deeply attuned to the needs of residents in her community. She oversees tribal programs that grant scholarships for children, assist elders with food, and provide other benefits.

“Our tribe really is here to help,” she explains. “That is our main job here, to help. And I think we’ve done a really good job with what we have.”

One of her most important duties is ensuring that King Cove residents have access to healthcare. She is frustrated that at present, access to lifesaving care is highly dependent on the weather.

“You get up in the morning,” she explains, “and you look around and say, ‘it’s super ugly out, I pray no one gets hurt today.’”

Kuzakin says that even in good weather, air travel can be traumatic for residents. So many people have experienced extreme turbulence, crashes, or near-misses that some must be medicated now in order to fly.

When aircraft cannot operate due to the weather, the next option is to travel by boat. But during a storm, ocean travel is also treacherous or impossible. Kuzakin says that elders, after surviving the harrowing trip by boat between the two communities, have had to be loaded into crab pots so that they could be hoisted onto dry land at Cold Bay.

“Crab pots!” she exclaims, shaking her head.

So much of the suffering, danger, cost, and indignity could be solved with a simple one-lane road. But one thing stands in the way: the Izembek National Wildlife Refuge, established in 1980 as part of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA). The refuge, which encompasses just over 300,000 acres, is home to one of the largest beds of eelgrass in the world. The Izembek Lagoon and surrounding wetlands host large populations of ducks, geese, eider, and other migratory birds. Environmental groups have fought hard to prevent the building of a road through this habitat.

Kuzakin agrees that the habitat is important but rejects the idea that the single-lane gravel roadway would cause significant harm. She points out that a roadway already exists, built during World War II by the United States military, so claims that a road could not be bult due to topographic challenges are hard to take seriously.

She also rejects the notion that King Cove residents secretly want the road for commercial use, or for recreation. Gas is expensive, she says. And residents have long agreed that the single-lane road could be designated non-commercial. King Cove’s thriving fishing industry, Kuzakin explains, prefers to transport product by boat and has no need for a one-lane road. Some environmentalists have even suggested that driving in bad weather is just as dangerous as flying or taking a boat in bad weather—a claim that Kuzakin dismisses outright as absurd. These, according to Kuzakin, are ignorant or bad-faith arguments made by outsiders who do not understand life in the Aleutian Islands. The purpose of the road, she says, is and always has been to help King Cove residents reach lifesaving care during emergencies.

“We want a road so that our kids and our grandkids, and my grandparents, and my mom can be safe. I don’t want to get up anymore in the morning and worry about the weather. And it’s something simple. It’s something super simple.”

King Cove resident and longtime road proponent Della Trumble agrees. As CEO of the King Cove Corporation, an Alaska Native village Corporation, Trumble has been fighting for the King Cove Road for decades and does not plan to stop until the community succeeds. As she drives through the lush green mountains outside of King Cove, their summits lost in a thick cloak of fog, Trumble comments on the long history of the Unangax̂ people living in the region.

King Cove resident and longtime road proponent Della Trumble agrees. As CEO of the King Cove Corporation, an Alaska Native village Corporation, Trumble has been fighting for the King Cove Road for decades and does not plan to stop until the community succeeds. As she drives through the lush green mountains outside of King Cove, their summits lost in a thick cloak of fog, Trumble comments on the long history of the Unangax̂ people living in the region.

Carbon dating has revealed that the King Cove area has been settled for at least five millennia, she says with pride. People who think the Unangax̂ should simply move somewhere with existing access to medical facilities don’t understand the history of the place and the connection that King Cove residents have with the land.

“We’ve had a presence here for thousands of years,” she explains, “and there’s no reason for us to move just because we want safer access, when that is something that the rest of the United States enjoys and has the benefit of.”

Trumble says that the Izembek National Wildlife Refuge was established entirely without the knowledge or input of the tribe or village corporation. King Cove residents were shocked to find agents of the federal government barring them from utilizing a natural subsistence resource that their community had managed for countless

generations. According to Trumble, after the Refuge was established, traditional subsistence cabins there were burned down.

“It’s crazy,” she shakes her head, “It’s crazy!”

Trumble bristles at the idea, advanced by some environmentalists, that the federal government knows how to manage the natural resources in their homeland better than the Unangax̂. And like many in King Cove, she finds federal regulations about game management deeply flawed and hypocritical. Subsistence users are barred from harvesting game from what is now a National Wildlife Refuge, but hunters from around the world are allowed to fly into Cold Bay and kill hundreds of migratory birds just outside the Refuge’s artificial and arbitrary borders.

Trumble is frustrated with the endless political gamesmanship over the right of the Alaska Native King Cove Village Corporation to develop a one-lane dirt road through their traditional homeland. Because the National Wildlife Refuge is managed by the federal government, an act of Congress would be required to allow the road. This has turned approval of the project into a political football, and caused parties to think less about the King Cove road as a discrete project and more about the legal implications of a decision that would allow its construction.

Powerful environmental groups are leery of any effort that would permit a road in a National Wildlife Refuge, fearing a precedent that would ripple out to other parts of the United Sates. Trumble doesn’t think environmentalists have much to worry about—the fight for a road permit has lasted for decades, and still has not been won. But this view has not swayed opponents.

In May 2022, former President Jimmy Carter, who signed ANILCA into law in 1980, thereby creating the Izembek National Wildlife Refuge, filed documents opposing a proposed land swap that would allow the road. According to Carter, ANILCA struck a “careful and lasting balance” between the need

to protect wilderness while also allowing development. Carter stated that allowing the King Cove Road to proceed would open the floodgates for protected wilderness all over the United States to be developed for any number of purposes.

Alaska politicians including Don Young, Frank Murkowski, Lisa Murkowski, and Ted Stevens have thrown their support behind the King Cove road, but it still hasn’t been enough to overcome resistance. Deals have been attempted, and failed. Land trades have been proposed, and rejected. Trumble suspects that some politicians and political appointees who visit the community have already made their minds up not to support the road.

At times, progress on permitting the road has seemed tantalizingly close, only to vanish in the eleventh hour. But despite setbacks, the community has not given up. For Trumble, the road is about protecting the most important things in life: families and community.

“We will continue to fight this battle until we get this road,” Trumble vows. “It’s never going away.”

Etta Kuzakin feels the same way. Kuzakin left King Cove to continue her education, but knew the town would draw her back. “I’ve always known that I wanted to live here and raise a family here,” she says. Kuzakin wanted her children to enjoy the same childhood she had in King Cove, growing up as part of a close-knit community that continues to practice indigenous ways of life. Kuzakin wanted to raise her daughters with the knowledge to gather subsistence foods, learn to use firearms, and know how to clean animals—just as her parents had taught her.

The King Cove Road is a critical part of that effort.

The King Cove Road is a critical part of that effort.

“It’s not just a road,” she explains. It is a lifeline for the entire community, from elders to fishery workers to young mothers to children. It is not just a strip of gravel as much as it is a physical manifestation of the community’s desire to care for one another and preserve their way of life for future generations.

To those who suggest that the community move, she replies, “I don’t have to live here. I’m honored to live here.”

While Kuzakin is frustrated with those who seem to value abstract or naïve beliefs about wilderness over the health and well-being of her community members, and disappointed by the lack of progress with permitting, she refuses to back down. “We’ve been fighting, we are fighting, and we will continue to fight,” she vows.

“Our communities are some of the most beautiful treasures we’re ever going to receive,” Kuzakin explains. King Cove is one of the few places where residents can still follow subsistence traditions that can be traced back continuously for thousands of years.

“We live in one of the most beautiful places on earth,” she says. “Unless it’s blowing 100…” she trails off with a laugh. “I love where I live. I love King Cove. I wouldn’t live anywhere else.”