To Speak

Keeping our Language and Identity Alive: Preserving Unangam Tunuu

Like many of Alaska’s Indigenous languages, Unangam Tunuu—the traditional language of the Unangax̂ people—was long imperiled, and preserving and teaching the language are important and serious tasks. However, there is at least one Unangam Tunuu word that is already known by people around the world: Alaska.

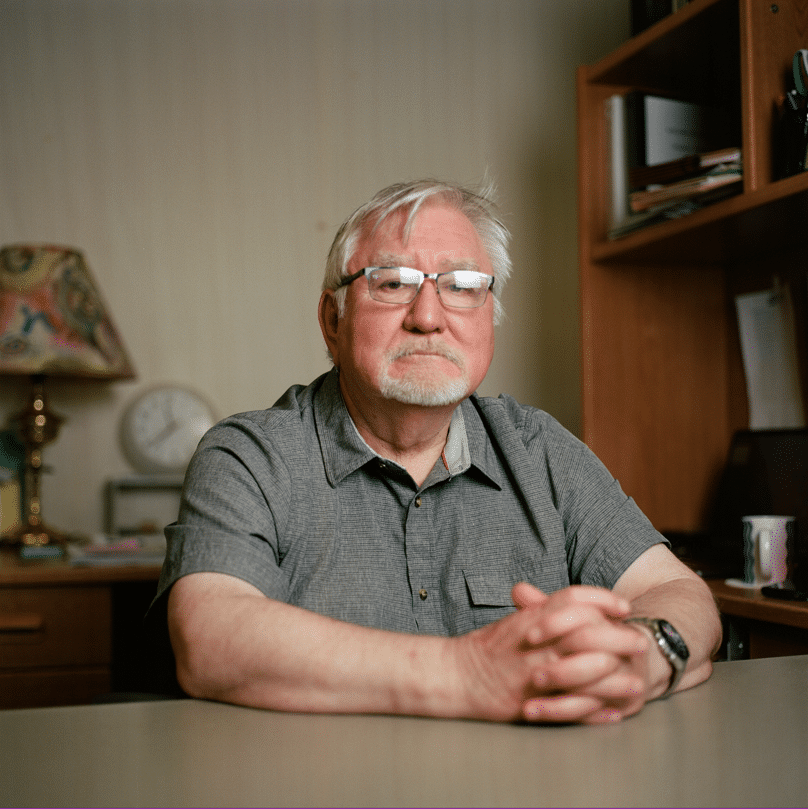

Moses Dirks explains that the name of America’s largest state was, in fact, derived from Unangam Tunuu Alaxsxix̂. The word is often translated as “the great land,” but Dirks argues that a more accurate translation is likely “the mainland.” The uncertainty surrounding the very meaning of a word as ubiquitous as “Alaska” is just one example of the challenges facing Dirks and others who have dedicated a significant portion of their lives to keeping Unangam Tunuu alive.

Dirks, now one of the world’s leading scholars of Unangam Tunuu, is uniquely qualified for the role. He was born in 1952 in Atka, and grew up on the island living a traditional subsistence lifestyle. He fondly recalls spending his childhood hunting, gathering, and fishing. Every summer, they had to stockpile enough food to help the community make it through the cold, windy winter. But despite the hard work, he enjoyed the traditional ways of life. “Growing up in Atka was very pleasant,” he says, “and full of life experience.”

His grandfather and other elders in the community spoke Unangam Tunuu fluently, and it naturally became Dirks’ first language. “You listen and learn,” he says.

Dirks did not encounter English until he went to school. The English language was very different from the Unangam Tunuu that he was familiar with—in some ways the languages are “opposites,” he says now. “It took me a long time to speak and use English grammar correctly.”

“I’m still learning a lot,” he says of English, with total sincerity.

After Dirks graduated from high school in the 1970, he met a professor from Oslo, Norway, who was studying the Niiĝuĝix (Atkan, but referred to as Central/Western) dialect of Unangam Tunuu. The researcher had worked with Dirks’ father and grandfather, and Dirks’ interest in language inspired him to work with the researcher. Dirks assisted with field work, gathering words for a dictionary, and recording folklore.

The partnership was successful, and the two men continued to collaborate for decades.

Despite his extensive scholarship, Dirks has remained ever curious and never assumes he has learned everything about the language. “I don’t consider myself an expert because I’m always a student of the language,” he says.

Dirks evolved his childhood love of language into a successful decades-long career working with Unangam Tunuu in different capacities for school districts throughout the Aleutians and in Anchorage. After retiring, he says, he was approached by Millie Jackson, the Cultural Heritage Director of the Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association, and asked to help lead a concerted effort to preserve and teach Unangam Tunuu.

Now, Dirks spends a considerable amount of time documenting, studying, and teaching Unangam Tunuu. The work, though rewarding, is not easy. One of Dirks’ primary goals is recording and gathering as much information as possible from elders who grew up speaking the language fluently. This can be a race against time, Dirks explains, as there are fewer and fewer first-language speakers as the years pass. He and his associates, he says, must “gather as much as possible, as fast as possible.”

“It’s much more challenging,” than it was in previous years, Dirks says. “You won’t be able to get as much Unangam Tunuu as we did in the past. But we’re trying. We’re trying really hard.”

As older generations pass on, younger generations are growing up with more access to global culture—and that means exposure to English. Mass media, including video games and television, Dirks says, are powerful forces pushing younger generations toward English and away from Indigenous language. Dirks laments the status of English as a “prestige language,” associated with status and political power.

Another challenge to the preservation and continuation of Unangam Tunuu simply comes from the profound rate of change in today’s technology and culture. Hundreds of years ago, Unangam Tunuu absorbed many Russian words due to the impact of Russian colonization and trade in the Aleutian Islands. The Unangam Tunuu words for kitchen utensils, Dirks provides as an example, are all derived from Russian. The deep effect of the Russian Orthodox Church has also introduced many Russian words into Unangam Tunuu language.

Now, integrating a torrent of new words—internet, satellite, electric car, meme, smartphone—while preserving the integrity of Unangam Tunuu is a never-ending task. Dirks explains that a committee of Unangam Tunuu speakers and learners meets to discuss how to shepherd the evolution of the language.

Of course, some of these changes to language are natural, Dirks says. All languages change over time, and Unangam Tunuu is no exception. Contemporary Unangam Tunuu, he explains, is different from what may have been spoken hundreds of years—or even a generation—ago. He tries his best to keep his own language traditional, however.

“I’m old school,” he says.

Unfortunately, some Unangam Tunuu has simply been lost. Colonization, including the forced removal of Indigenous languages, strict enforcement of the English language, and forced relocations from ancestral lands, has wreaked havoc on the process of passing the language on to younger generations. Dirks notes that of the nine original Unangam Tunuu dialects, only two remain. Dirks wants to help halt this process by carefully preserving what remains. And just as importantly, he wants to pass the language on to the next generation.

Dirks says he has tried to teach many younger people in the community their ancestral language, but this isn’t always easy. Some young people, unfortunately, are not interested. However, recently he has seen an intentional shift toward learning the language in younger generations.

“Hopefully this time around,” he says, “there’s a lot of interest in Unangam Tunuu, as far as revitalization goes. So, it’s good to see there are younger people taking up an interest in the language. I just hope they keep it going.”

Dirks believes that younger people in the community have a responsibility to keep their language alive. “I think it’s important to learn and use the language and study it,” he says, “and learn more about it. As I was growing up, I thought that each individual person who spoke the language—I thought that was their responsibility. To keep the culture and language going. And try to preserve it and then use it, so it doesn’t get lost.”

Ultimately, Dirks explains, he believes that preserving Unangam Tunuu is essential for keeping Unangax̂ culture and traditions alive. “The language itself defines who we are,” he says. “I think it’s a very important component of our survival as people.”

Dirks prefers the term Unangax̂ to describe himself over the term “Aleut.” Nobody is certain where the word Aleut came from, he explains. As a lifelong student of Language, Dirks prefers the term that comes from his ancestral people to describe himself.

Establishing self-identity and critiquing—or rejecting—identities imposed by outside forces is also a central part of Haliehana Stepetin’s work.

Stepetin, who is being mentored by Moses Dirks in Unangam Tunuu, is visiting Akutan as part of her PhD research. She walks into the Akutan museum and reaches up to adjust a pelt that has slumped down on the wall. “This has to be restored,” she says.

On the walls, Stepetin gestures toward a wall of colorful tiles painted by children who grew up on the island. “That’s the one that I did!” she says with a laugh, pointing at one tile toward the bottom of the wall. “I was like four!”

Stepetin walks through the museum’s collections, noting an old sign for Wakefield, an early fish processor in the Aleutian Islands, artifacts, and a fox trap. Display cases hold arrowheads, many archival photos, and a Yup’ik basket.

Stepetin is back on Akutan, where she grew up, on a fellowship from the Social Science Research Council, she says. Without the fellowship, it would have been difficult or impossible to conduct her research in the time needed. Being here in person—and accessing the museum’s collections—were vital for her PhD research.

Her research, she says, involves demonstrating how the people of Akutan and other Unangax̂ communities of Unangam Tanangin (Aleutian Islands) have always lived sustainably, in balance with their environment. Stepetin believes that Indigenous practices may have lessons that can be applied to contemporary global problems like climate change.

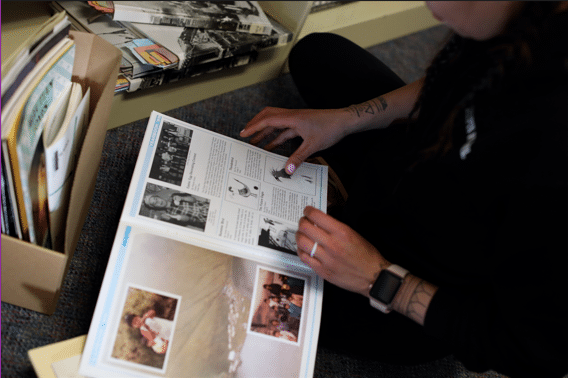

Stepetin reaches the library, where rows of books are neatly organized on several sets of shelves. Some of these you “can’t find anywhere else,” she says, pulling several volumes off a bottom shelf. One, called “Akutan Whaling Station,” appears to be printed on printer paper and is spiral bound. Another is a firsthand account of Atka’s early schools, which were founded in the nineteenth century. She pulls out another book, which includes two large black and white photos of the town in days long past. “That’s so Akutan,” she says, breaking into a wide smile.

A major aspect of Stepetin’s work, she explains, is countering misconceptions about Unangax̂ people that have proliferated because so much early writing about Unangax̂ culture was done by individuals outside of the culture. Russians, for example, wrote many of the earliest surviving texts about Unangax̂ people, but they often failed to truly understand who they were writing about.

A major aspect of Stepetin’s work, she explains, is countering misconceptions about Unangax̂ people that have proliferated because so much early writing about Unangax̂ culture was done by individuals outside of the culture. Russians, for example, wrote many of the earliest surviving texts about Unangax̂ people, but they often failed to truly understand who they were writing about.

Stepetin is critical, for example, of the English word “subsistence.” This American term, she explains, is insufficient to encapsulate the complicated and deep interaction and connection between Unangax̂ people and their environment. Subsistence, she explains, is not just a way to eat. It is a way of life.

Stepetin wants Unangax̂ history to be written by Unangax̂ people. She frequently interviews elders, and has contributed to documenting Unangax̂ traditions. Of course, she does not believe that only Unangax̂ people can write about Unangax̂ culture; the author Ray Hudson, she notes, is not Native but spent extensive time in Unalaska. “So I trust his work,” she says, “because he put Unangax̂ voices and stories first.”

Stepetin teaches Unangam Tunuu courses at the University of Alaska Anchorage, though she laments that it is difficult to pack language instruction into a conventional academic semester system.

As she explains her views toward language instruction, her phone rings. “Oop!” she exclaims, “It’s time to go.” She stands up with a smile, cradling an armful of books.

“I gotta go fishing!” she says.

***

To access Aleutian Pribilof Island Association’s (APIA) Unangam Tunuu Resources, follow the below link: https://www.apiai.org/departments/cultural-heritage-department/culture-history/

Contact UAA for more information If you’re interested in enrolling in Haliehana Stepetin’s Unangam Tunuu course: https://www.uaa.alaska.edu/.