Cats wearing birthday hats, dancers showing off new moves in public, hip-hop mashups of classic movies: this is the stuff that viral videos are made of. But recently, social media gave us something new to look at when Josephine Shangin, from Akutan, Alaska, went live on Facebook to show the world how to braid seal intestine.

“A bunch of friends in Anchorage were like ‘hey go live, I want to watch,’” she says with a laugh.

The live stream was a success.

Shangin, who has made it part of her life’s work to keep subsistence food traditions alive, says she enjoyed the ability to “share processing traditional foods with those who aren’t in our homelands or able to participate in person. They can participate virtually.”

Shangin grew up in Akutan, and has fond memories from her childhood. “It was fun growing up here,” she explains, “all the freedoms, you know? You’ve heard the saying ‘it takes a village to raise a child’? It was basically that. All of us kids, out from dawn until dusk, picking berries if we’re hungry… all the gathering and harvesting and hunting. It was a great way to grow up here. So I brought my kids back. I wanted them to experience the same thing.”

Reinvention

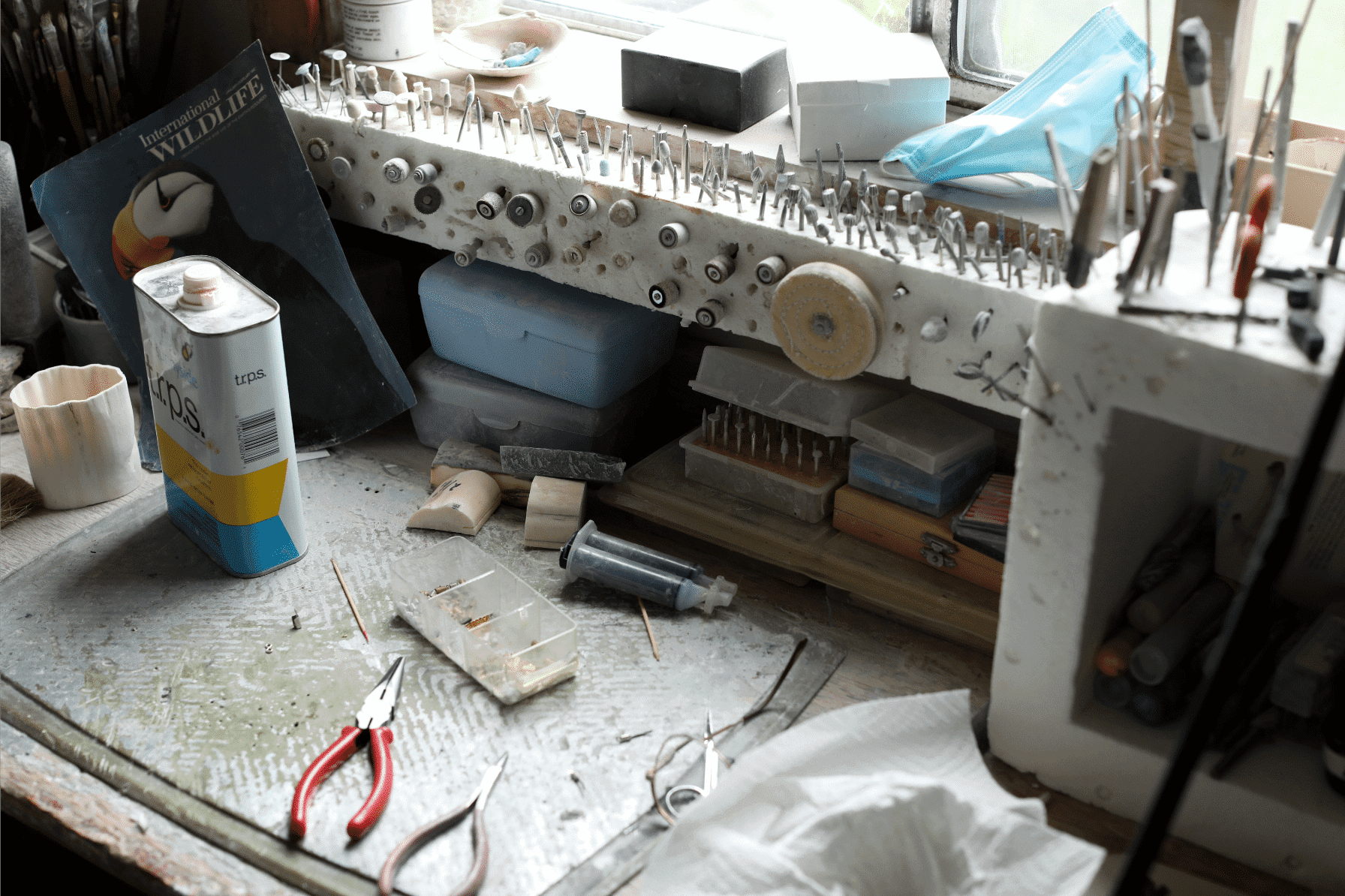

Beautiful sculptures, bentwood hats, jewelry, and weavings created by Gertrude Svarny fill museums and private collections throughout Alaska. To name a few of her accomplishments as a renowned Unangax̂ artist, Gertrude has won several Best in Show prizes at the Trail of Tears Art Show for sculpting. She was awarded the Distinguished Artist Award from the Rasmuson Foundation in 2017, and she has sat on the board of the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Gertrude Svarny is widely respected for her contributions to preservation, awareness, and education for Unangax̂ culture and art.

Now 92, Gertrude sits in her comfortable Unalaska home surrounded by artwork. But her path to becoming one of Alaska’s foremost Alaska Native artists was long and, in many ways, unexpected. It includes a childhood filled with joy and hardship, a passion for reviving Unangax̂ cultural practices, and a chance encounter with a whale bone.

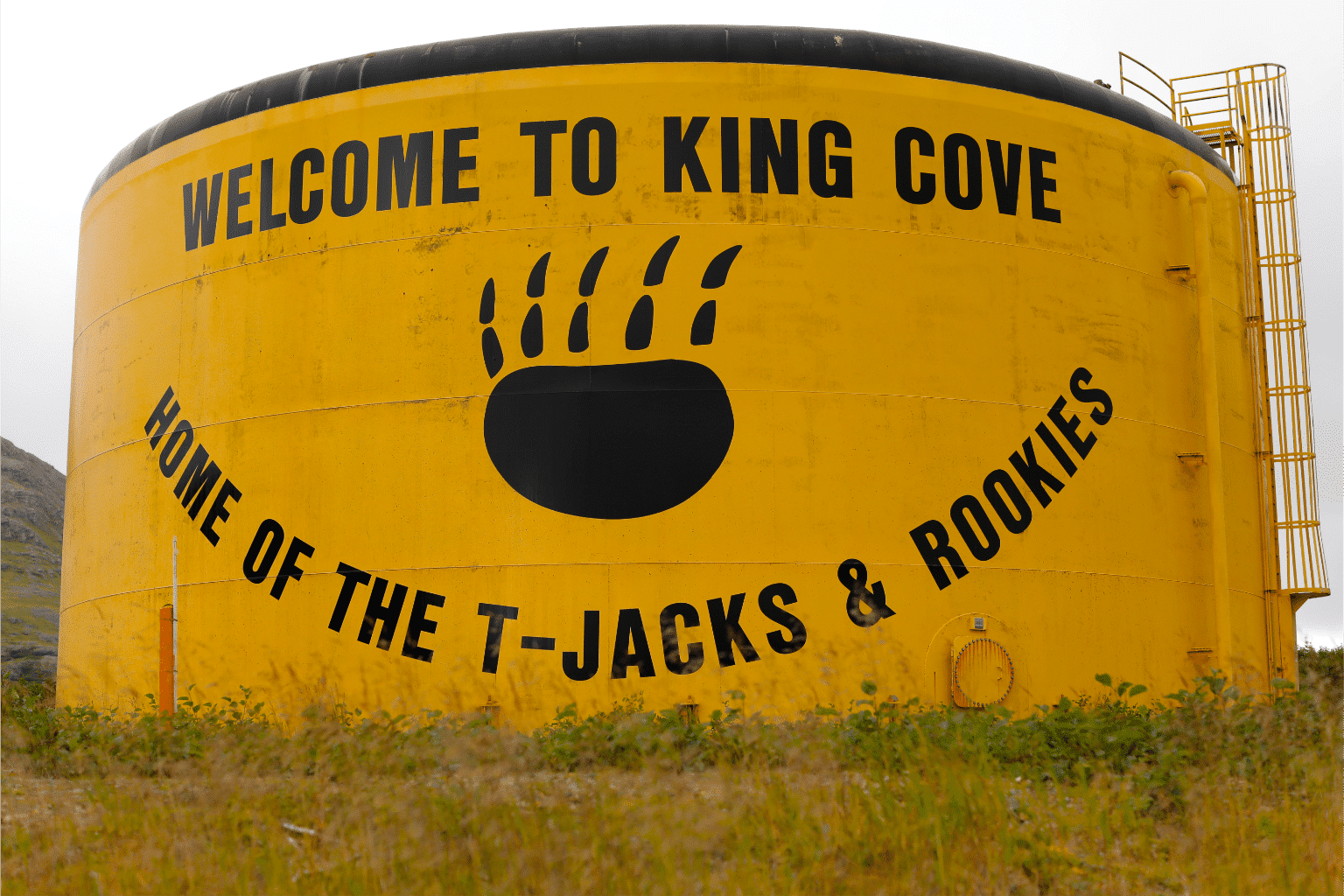

When Etta Kuzakin unexpectedly went into labor with her third child, she faced a terrifying choice. In most American towns, getting to a hospital for a C-section operation would be a matter of simply driving to the nearest hospital. But Kuzakin didn’t live in an ordinary American town. She was in King Cove, Alaska, a village of about a thousand in the Aleutian Islands, and reaching the nearest hospital would require a medevac flight from the town of Cold Bay. Though the large runway at Cold Bay was only fifteen minutes away by air, poor weather made traveling by aircraft or boat all but impossible.

And so Kuzakin was faced with a choice: should medical personnel in King Cove prioritize her life, or the life of her child?

For Kuzakin, who now serves as the president of the Agdaagux Tribe of King Cove, there was only one option. “So, I made sure the medical staff understood that if something happened, they should take my life and not my daughter’s,” she says, struggling to hold back tears even years later. “Because as a mom that’s what you have to do.”

Inaccessible

Finding Lessons in the Everyday: Challenges of Education in the Aleutians

Candace Nielsen’s three children rush into the room, full of smiles. She asks them about their day. “We saw five cows!” reports her elder son proudly, as he brandishes a gray plastic sword. Her younger son is slightly shy, but curiously looks around the room. The family pulls out a whiteboard and begins a language exercise.

“If they’re really good,” says Nielsen, “sometimes I let them get on the internet and stream a show.”

Though the scene might come from anywhere in America, it is unfolding in a place that is far from ordinary. Nielsen and her family live in Cold Bay, a community of less than one hundred located near the western edge of the Alaska Peninsula. Education in communities like Cold Bay is a constant challenge, and requires persistence, adaptability, and creativity.

Breakwater

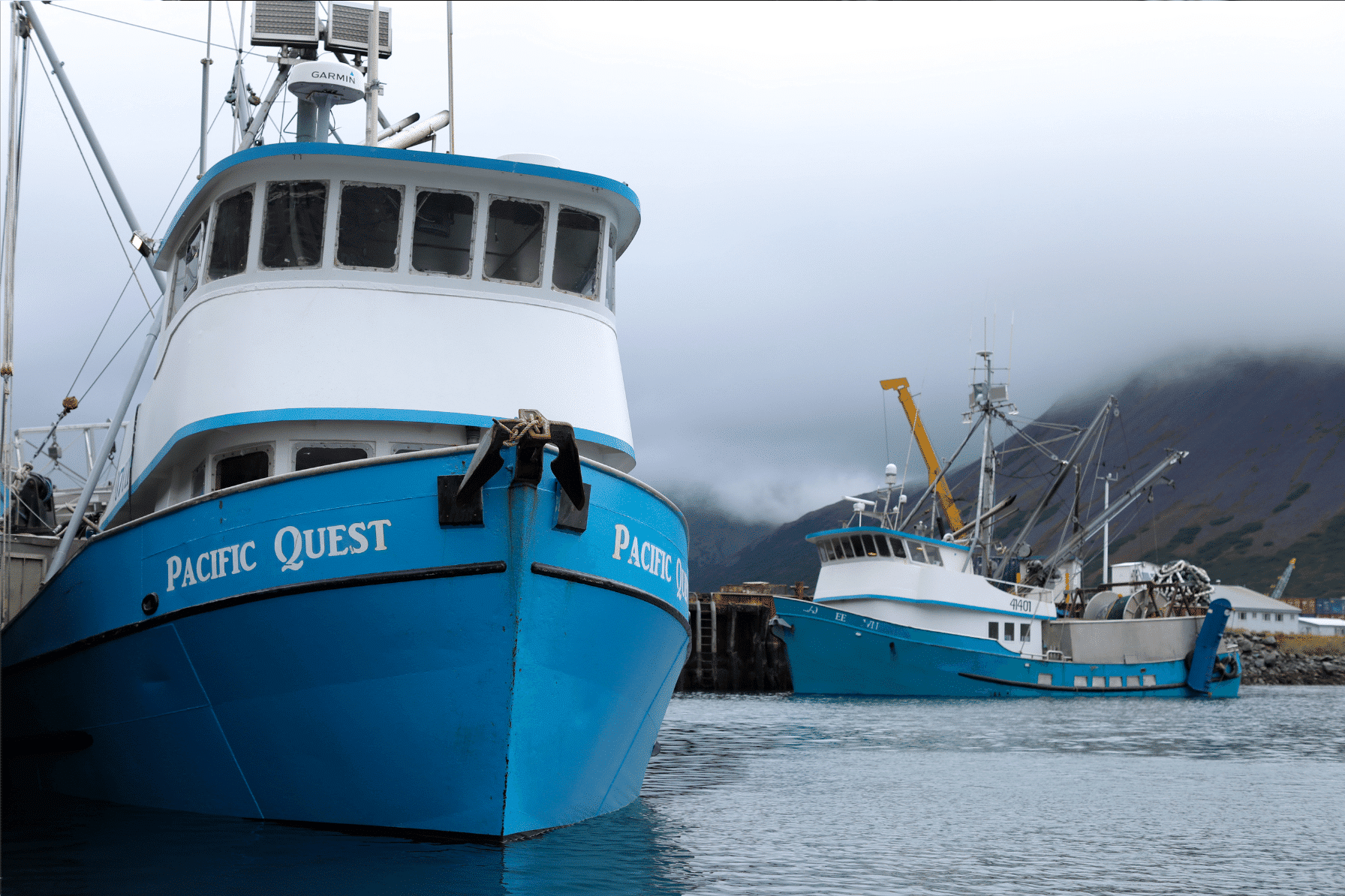

Adaptation: Fishing and Family in the Aleutians

A big motor emits a low, steady purr as the fishing boat crawls steadily forward, leaving swirls of dark water churning in its wake. In the distance, the green mountains and slopes of the Aleutian Islands rise gracefully out of the Pacific Ocean before fading into low clouds.

The boat is painted bright white, with light blue trim. It is the kind of old but well-loved vessel that one might expect to find on a postcard. But this is a true working boat, designed and operated with stark utilitarian efficiency in pursuit of one central goal: catching fish. Lots of them.

In the wheelhouse, the Captain, Kenny Bob Mack, recalls his first days in the industry over four decades, “I was just a young guy,” he says. After 43 years of fishing, he tried to retire several years ago. “I quit three years ago!” he claims, breaking into a wide, boyish smile. When friends and family try to remind him of his retirement, he jokes that his memory is going, and he cannot help but get back on his boat. To many in the Aleutian Islands, fishing is almost synonymous with life itself.